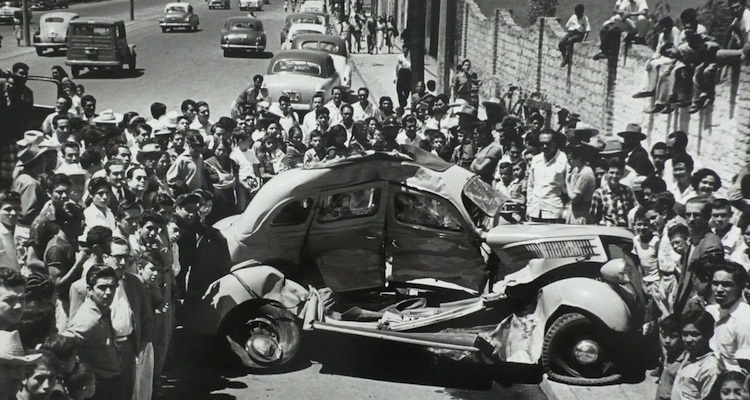

In 1942, when Enrique Metinides was eight years old, his father gave him a camera. The family lived near a police station in Mexico City. A year or so later, the cops let little Enrique inside so he could take his first picture that would be published in the newspapers: that of a detective holding up the severed head of a man who had been murdered in the neighborhood. For the next fifty years Metinides would take pictures for the police blotter section of the city’s grisliest newspapers. He shot photos of people who had been shot, stabbed and bludgeoned to death; of children whose hands had been mangled in meat grinders; of cars and buses that had crashed and been split in two. He took pictures of train derailments, airplane crashes and gas explosions. All of them were influenced by the black-and-white movies he saw as a child. Enrique Metinides: The Man Who Saw Too Much, a retrospective exhibition of his work, is being shown at the FotoMuseo Cuatro Caminos (Ingenieros Militares 77, Lomas de Sotelo, Naucalpan, Edo. de México). Curated by my friend Trisha Ziff, it’s an incredible show — a sort of collective catalogue of our traumas. Don’t miss it. Trisha also directed a breathtaking documentary about Metinides, also called El hombre que vio demasiado, which will be shown at this year's Ambulante documentary festival. Click here for the schedule.

Goodbye to El Caballo

When I first visited Mexico City in the late 1980s, there were no multiplex cinemas like Cinemex and Cinépolis. You saw movies at ratty-ass theaters that cost about a dollar per ticket, projected films in a strictly out-of-focus fashion, and with sound systems that threw voices at different areas of the house at will. Projectionists sometimes were oblivious as to whether they were showing the third reel first, or the fifth reel second. When you stood up to leave at the end of the movie, your shoe would be stuck to the floor with Coca-Cola that had been spilled in the era of Pancho Villa.

Among the films I saw in those days were sex comedies with titles such as Un macho y sus puchachas and Dos nacos en el planeta de las mujeres. They tended to feature male characters who tried to have sex with as many women (as incredibly sexy as they were compliant) as possible -- no matter whether they were the wives of their best friends -- meanwhile trying to avoid work at all costs. I believe these movies depicted the aspirations, if not the reality, of a significant part of the audience. If they were morally indefensible, the films were indisputably funny. I remember once my Mexican ex-wife scolded me for enjoying these things. I connived to get her to watch one with me, and was relieved to hear her laugh loudly and often.

A skinny character called Alberto Rojas "El Caballo" pranced, skipped, slid and skidded through many of these pictures as a protagonist. He racked up as many conquests as the rest of the cast, but in a more underhanded fashion, usually getting women on his side by "pretending" to be a sashaying, ass-shaking hairdresser, or indeed by dressing as a woman. (Some would say that this duality confirmed a secret reality or at least a desire of a significant segment of Mexican machismo.) Rojas's comedic timing and split-second command of albures -- Mexican double entendres -- served the dual purpose of reliably making me smile and helping me learn the (no pun intended) ins and outs of Mexican slang.

Rojas died of cancer last Sunday at the age of 72. I had the good luck of running into him in the Mexico City airport a few years ago, and having the opportunity to tell him how important he was in terms of my education in Mexican culture. He seemed quite amused at the idea of having a gringo fan with a strange accent.

Bye bye Bowie

When I was 20 years old, I lived in New Orleans and waited tables at a place in the French Quarter called the Café du Monde. Nearly every tourist who passed through the city stopped there, to sample French doughnuts called beignets covered in powdered sugar, and café au lait mixed with chicory. I worked the shift between midnight and eight in the morning, mostly waiting on drunks, but so avoiding the busloads of sightseers who trooped in during the day and early evening. One night a startlingly beautiful man arrived with what was clearly his retinue of three or four other people. They all ordered coffee but eschewed the beignets. The beautiful man -- who earlier that night had played a concert in Baton Rouge -- was in one of his more conservative periods, his hair straight and parted on the side, dressed in a brown jacket, a plaid shirt and a woven necktie. I realize that this is dating me, but this was back before he got his teeth fixed. The crooked choppers were the only imperfection in an otherwise flawless appearance, and sort of served as a reminder that he was an actual human being and hadn't arrived from Olympus.

Now I am really dating myself: in those days, the total charge for all of their coffees was $2.98. After I served them, one of the group gave me $3.00 and told me to keep the change. I never blamed David Bowie for getting my tip stiffed from me. The boor was a member of his entourage; the man who sold the earth couldn't have been bothered to handle the money.

The writing on the wall

Photos by Adam Peacock

I noticed these two signs walking through Coyoacán not long ago. For the Spanish-impaired, the one on top says "One in five workers cannot afford the basic basket" (which refers to a set of groceries, such as eggs, milk, bread, beans and tortillas, which are supposed to be subsidized by the government here). The one on the bottom says, "One per cent of the population has half of the national wealth." Have a happy new year, everybody.

Mexican humor

A doughnut stand, seen recently in the metro. Opera fans, take note.